Prosecutorial Inconsistency: Doublethink in the Courtroom

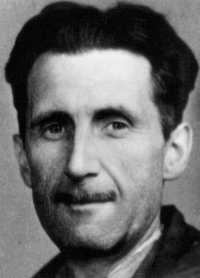

"To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, . . . to forget whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again: and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself. That was the ultimate subtlety: consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. Even to understand the word "doublethink" involved the use of doublethink."

"To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, . . . to forget whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again: and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself. That was the ultimate subtlety: consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. Even to understand the word "doublethink" involved the use of doublethink."George Orwell, "1984."

My client is awaiting trial on a charge of assault with a deadly weapon. He apparently gave the police a tearful confession describing how he stabbed the victim one time with a pocket knife during a street brawl and then disposed of the knife. One small problem . . . I just learned that another young man recently pled guilty to a charge of assault with a deadly weapon arising out of the same incident. The factual basis for that plea was the victim's statement to the police describing how that defendant inflicted the victim's only wound with a pen.

May the prosecutor vouch for the veracity of my guy's "confession" when it is factually inconsistent with the basis of the other guy's charge and plea? I believe In re Sakarias (2005) 35 Cal.4th 140 says no.